Moving to a new country is often imagined as a fresh start. New opportunities, new people, new landscapes. In the early days, everything feels exciting.

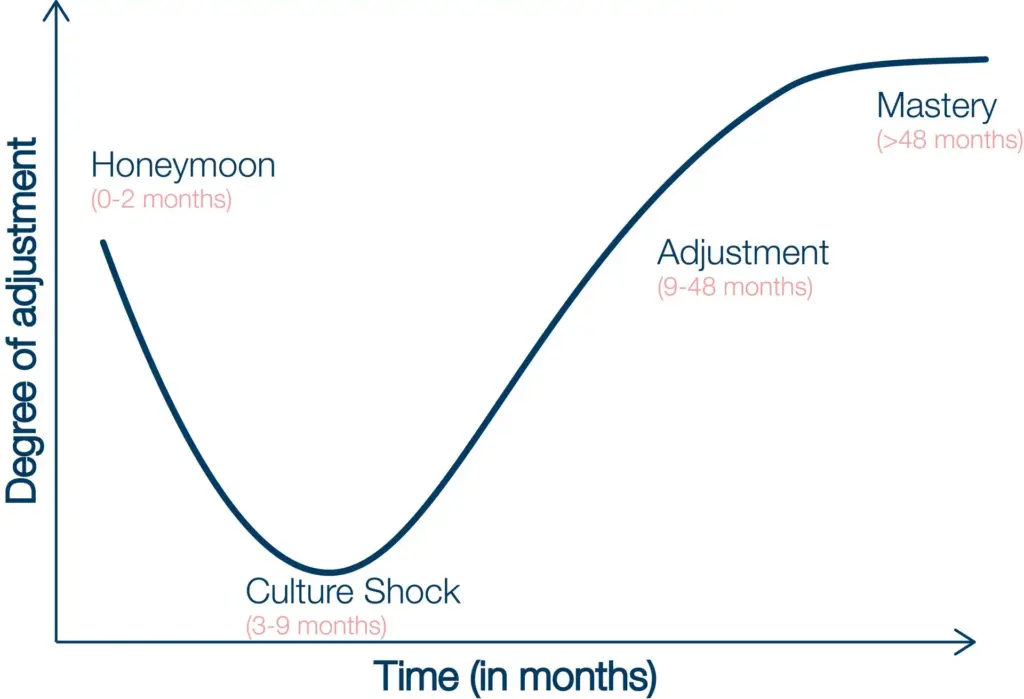

Psychologists have long observed that this emotional journey often follows a predictable pattern. It is known as the U-shaped curve of cultural adjustment.

First described in 1955 by sociologist Sverre Lysgaard, the model suggests that people who relocate internationally tend to experience an emotional trajectory shaped like the letter U: an initial high, followed by a decline, and eventually a recovery.

Phase One: The Honeymoon

The first phase is often referred to as the honeymoon stage.

During the first weeks or months after arrival, many people experience heightened enthusiasm. Differences feel fascinating rather than frustrating. Everyday experiences such as language, food, architecture, and social customs can feel stimulating and positive.

This period is often characterized by curiosity and optimism. The challenges of relocation exist, but they are filtered through novelty.

For some individuals, this phase may last a few weeks. For others, it may extend to two or three months.

Phase Two: Culture Shock

After the initial excitement fades, reality becomes more visible.

Daily tasks become more complicated. Language barriers create friction. Administrative systems feel unfamiliar. Social networks are limited. Small misunderstandings accumulate.

This period is commonly called the culture shock phase.

Emotionally, it can involve frustration, loneliness, irritability, or homesickness. People may begin to question their decision to move. A sense of not belonging often becomes stronger.

Psychologists describe this phase as a confrontation between expectations and lived experience. The novelty effect disappears, and practical challenges dominate.

For many expatriates or international students, this phase tends to emerge somewhere between several months after arrival, particularly between three to nine months.

Phase Three: Adjustment and Adaptation

Over time, coping strategies develop.

Language improves. Routines stabilize. Social connections deepen. The host culture becomes more predictable. Confidence gradually returns.

This stage marks the upward slope of the U-curve.

Rather than constant emotional highs, individuals experience increasing competence. The new country no longer feels entirely foreign, but it may not yet feel fully like home.

Research suggests this adjustment phase can take months or even several years, depending on personality, support systems, and cultural distance.

Phase Four: Mastery

Long-term adaptation represents stabilization at the top right of the U.

After extended exposure, individuals often develop bicultural competence. They understand social norms intuitively, navigate institutions comfortably, and maintain meaningful relationships.

At this stage, emotional volatility decreases. The new environment becomes integrated into identity rather than experienced as external.

Some researchers argue that full integration may take several years, sometimes more than four. Others note that adaptation is rarely linear and may fluctuate with life events.

Is the Model Universal?

The U-shaped curve is widely cited, but it is not a rigid law.

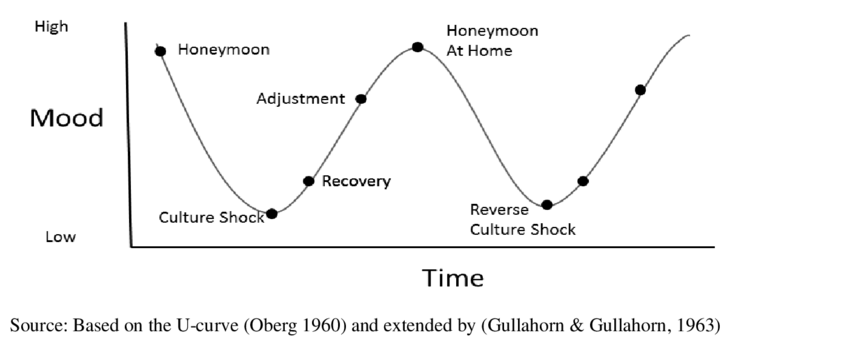

Later research has suggested variations, including a W-shaped model that adds a second dip upon returning home. Some scholars argue that adjustment is more dynamic and individualized than a simple curve suggests.

Nevertheless, the honeymoon, culture shock, and adaptation framework remains influential in cross-cultural psychology, migration studies, and international business training.

Why the Decline Happens

The dip in the middle of the U is often misunderstood.

It does not necessarily mean the move was a mistake. Instead, it reflects cognitive and emotional adjustment to new norms.

Humans rely heavily on predictable social cues. When those cues change, mental energy increases. Simple tasks require more effort. Social identity becomes uncertain. This cognitive strain contributes to stress and reduced well-being.

Over time, as new patterns become familiar, mental load decreases. Emotional stability returns.

The Larger Lesson

The U-shaped model does not guarantee that every relocation ends positively. Nor does it imply that everyone will experience severe culture shock.

What it suggests is that emotional turbulence during relocation is normal rather than exceptional.

Understanding this curve can help individuals interpret their experience with more patience. The low point in the middle is often part of the process, not its conclusion.

Moving abroad reshapes routines, identity, and belonging. The emotional journey may dip before it rises. For many, adaptation is not about returning to the initial honeymoon, but about building a different and more grounded sense of home.