Stagflation is one of the most uncomfortable conditions an economy can face. It describes a situation where economic growth slows or stalls, unemployment rises, and inflation remains high at the same time.

Under normal economic logic, inflation and weak growth do not usually move together. Inflation is often associated with strong demand and expanding economies, while recessions tend to reduce price pressures. Stagflation breaks that pattern. It combines stagnation with rising prices, creating a difficult environment for households, businesses, and policymakers.

The Definition

The term “stagflation” merges two concepts: stagnation and inflation.

It typically includes three elements:

- weak or negative economic growth

- high or rising unemployment

- persistent inflation

This combination creates a policy dilemma. Measures that reduce inflation, such as higher interest rates, can further slow growth. Measures that stimulate growth, such as lower interest rates or increased government spending, can worsen inflation.

Because of this tension, stagflation is considered particularly challenging to manage.

Historical Example: The 1970s Oil Shock

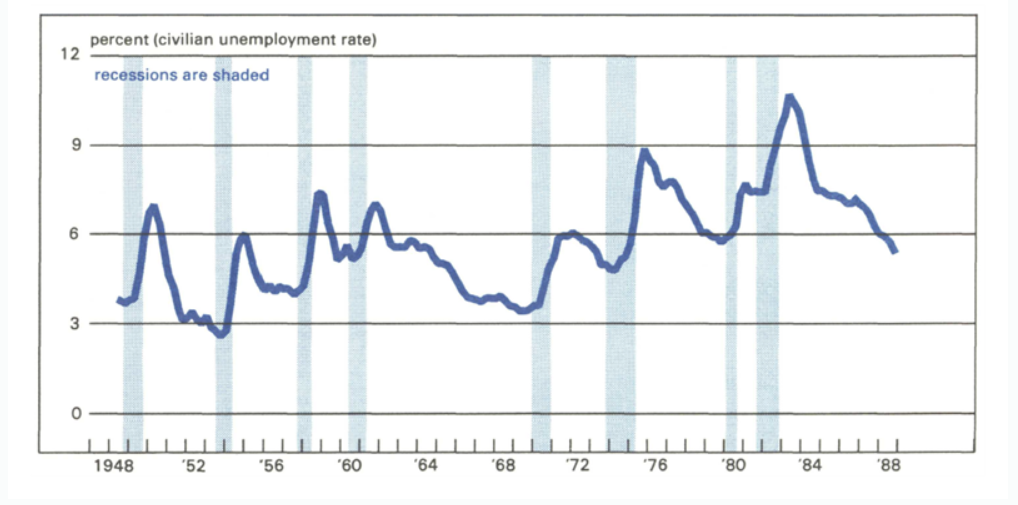

The most well-known example of stagflation occurred during the 1970s in the United States and several European economies.

Following oil supply disruptions in 1973 and again in 1979, global energy prices surged. Oil is a key input for transportation, manufacturing, and heating. When its price rose sharply, production costs increased across the economy.

At the same time, economic growth slowed. Higher energy costs reduced business margins and consumer spending power. Unemployment increased. Yet inflation continued to rise because input costs remained elevated.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

In the United States, inflation exceeded 10 percent during parts of the decade, while unemployment also climbed significantly. Many European countries experienced similar pressures.

The episode challenged existing economic theory at the time, which assumed that inflation and unemployment had an inverse relationship. Stagflation demonstrated that supply shocks could push both higher simultaneously.

What Causes Stagflation?

Stagflation is often triggered by supply side shocks rather than demand surges.

Common triggers include:

- sharp increases in energy prices

- disruptions to global supply chains

- geopolitical conflicts affecting key commodities

- large increases in input costs

When production becomes more expensive, businesses may pass those costs on to consumers. Prices rise even if demand is weak. At the same time, higher costs can force firms to cut investment or employment, slowing growth.

Another contributing factor can be prolonged loose monetary policy combined with external shocks. If inflation expectations become embedded in wage negotiations and price setting, inflation may persist even as growth weakens.

Which Sectors Feel Stagflation First?

Stagflation does not affect all parts of the economy equally.

Energy and food are often among the first areas where price pressures appear. Both are highly sensitive to global supply disruptions and input costs. When oil, gas, or agricultural commodities become more expensive, the effects spread quickly through transportation and consumer goods.

Manufacturing can also be heavily affected, particularly industries dependent on imported raw materials. Rising costs combined with falling demand can compress margins and reduce output.

For households, essentials such as fuel, food, and housing typically absorb a larger share of income during stagflation periods. This reduces discretionary spending and weakens retail and services sectors.

Financial markets may also experience volatility. Bonds can suffer from rising inflation expectations, while equities may face pressure from weaker earnings growth.

Why Stagflation Is Difficult to Address

Central banks normally use interest rates to control inflation. Raising rates reduces borrowing and spending, helping to cool price growth. However, during stagnation, higher rates can deepen economic slowdown.

Governments may try fiscal stimulus to support employment and growth. Yet if supply constraints remain unresolved, additional spending can intensify inflation rather than relieve it.

This tension means that policy responses must carefully balance inflation control with growth stabilization. In the 1980s, several central banks adopted aggressive interest rate hikes to break inflation expectations, accepting short-term economic pain in exchange for longer term stability.

Is Stagflation Common?

Historically, stagflation is relatively rare compared to standard business cycles. Most recessions are accompanied by falling inflation, and most high inflation periods occur during strong demand.

However, modern economies remain vulnerable to supply side disruptions. Globalized supply chains, energy dependence, and geopolitical risks can create conditions where price pressures persist even as growth slows.

Periods of high energy prices combined with weak productivity growth can also raise stagflation concerns.

The Economic Trade Off

Stagflation highlights a structural reality: inflation does not always signal strength, and weak growth does not always guarantee price stability.

When inflation is driven by supply constraints rather than demand expansion, traditional policy tools become less effective. Addressing the underlying supply problem, whether energy availability, production bottlenecks, or labor market mismatches, becomes essential.