Between 1845 and 1852, Ireland endured one of the gravest disasters in modern European history. Known in Irish as Gorta Mór, the Great Hunger caused the deaths of about one million people and forced another million to leave their homes. The population fell from more than eight million in 1841 to roughly six and a half million a decade later. The famine began with a crop disease, but its impact reached far beyond agriculture. It exposed deep inequalities in land ownership, governance, and social structure that had built up under British rule.

Potato and the Fragile Balance of Rural Life

To understand the famine, one must understand the place of the potato in Irish society. By the 1840s, nearly half of the population depended on it as the main source of food. It was easy to grow, nutritious, and suited even to the poorest soils. A single acre could feed a family for a year when supplemented with a little milk. Entire rural communities were built on this simple diet, which provided energy and health despite its simplicity.

This reliance also created a fragile balance. Many families rented only a few acres from large landlords and had little income beyond what they could grow. Rent was paid in cash or crops, leaving little to sell or store. When the potato crop failed, people did not merely lose one type of food; they lost the foundation of their daily survival.

The Arrival of the Blight

In September 1845, reports spread of a strange disease affecting potatoes across Europe. In Ireland, the blight struck with shocking speed. Fields that appeared healthy in the morning were blackened by evening. The tubers rotted underground, leaving a foul smell and nothing to harvest. Farmers tried to replant in 1846, but the infection returned with even greater force. In that second year, three-quarters of the crop was destroyed.

By winter, hunger was widespread. Families ate seed potatoes, wild plants, and even seaweed along the western coast. As food prices rose, people began to sell their clothes, tools, and livestock to buy meals. When these resources were gone, they turned to the workhouses, which soon overflowed.

The Economy Before the Famine

In the decades before the crisis, Ireland was an overwhelmingly rural country. Most families survived by renting small plots of land from landlords, many of whom lived in England and collected rents through agents. The potato was the foundation of daily life. It was productive and nutritious, allowing families to sustain themselves even on tiny pieces of land. However, this dependence also created a fragile balance. Nearly half of the population relied on the potato as its main food source, which made the economy extremely vulnerable to crop failure.

When the potato blight reached Ireland in 1845, it infected large parts of the harvest. Farmers replanted the following year, but the disease returned with even greater intensity. By 1846, the crop had almost entirely failed in many regions, and hunger began to spread rapidly.

Relief, Policy, and Market Beliefs

Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, and British authorities responded with policies shaped by the economic thinking of the time. The government preferred market-based solutions and was hesitant to interfere directly with food prices or trade. Public works programs were launched so that people could earn wages to buy food, but pay levels were low and conditions were harsh. As the famine deepened, these schemes collapsed under their own weight.

Private grain exports from Ireland continued under contract, and imported maize, known as “Indian meal,” arrived from North America. However, the poorest could not afford it. What emerged was a crisis not because of the absence of total food but of economic access. The relief effort was later supported by soup kitchens and local charities, but the scale of suffering far exceeded available aid.

Help from Abroad

Support also came from outside the British Isles. Donations were collected in the United States, France and other parts of Europe. Religious groups, including Quakers, organized direct assistance through soup kitchens and local committees. Among the most notable gestures was the contribution from the Ottoman Sultan Abdülmecid I, who offered financial support to Ireland in 1847.

Historical records from both Irish and Ottoman sources confirm that the Sultan initially intended to donate £10,000 to relief efforts. The British government, concerned with diplomatic protocol since Queen Victoria had publicly donated £2,000, requested that he reduce the sum. Abdülmecid agreed and sent £1,000 officially, which was received by the British relief fund. Several reports also describe Ottoman ships bringing food supplies to Irish ports, including Drogheda, where the gesture is still remembered today through a commemorative plaque.

While the amount of aid was modest compared with the scale of the disaster, the Ottoman donation symbolized international compassion and remains one of the earliest recorded acts of cross-continental humanitarian relief.

Economic and Social Transformation

The famine permanently changed Ireland’s economic structure. The smallholdings that had supported tenant families disappeared as many were unable to pay rent. Land ownership became concentrated into larger estates focused on livestock rather than crops. The Encumbered Estates Acts of 1848 and 1849 allowed heavily indebted landlords to sell their properties, accelerating this transformation.

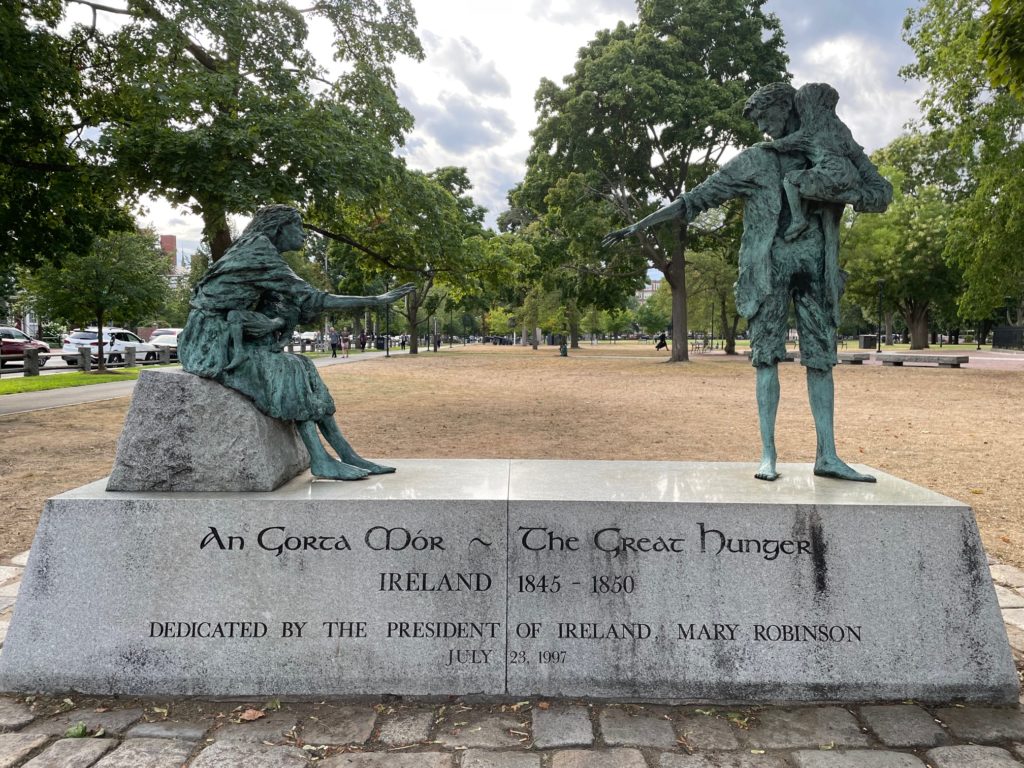

Emigration reshaped Irish society. Entire communities left for North America, and the Irish diaspora became one of the largest of the nineteenth century. By the early 1850s, more than two million people had emigrated. The loss of population reduced labor supply and altered the social fabric of rural Ireland for generations.

Political Consequences

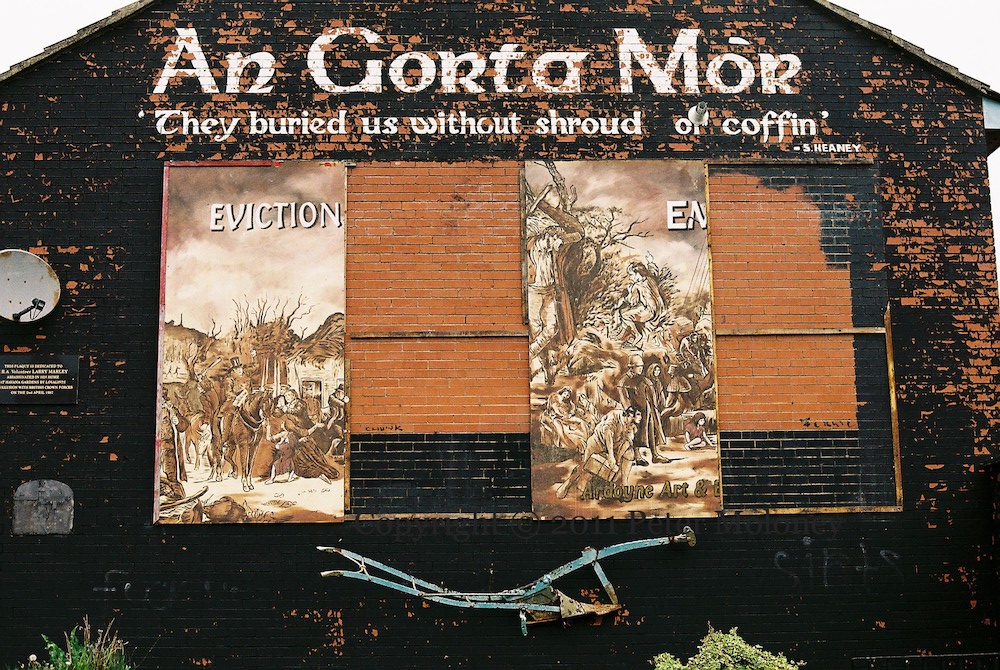

The famine also left a deep mark on Irish political life. Many people viewed the government’s response as inadequate and indifferent. This perception strengthened the belief that Ireland’s future could not depend on decisions made in London. The memory of Gorta Mór became a central part of Irish national identity and later fueled the demand for self-government.

The Legacy

When the famine ended in the early 1850s, Ireland was a changed country. Its economy became less dependent on the potato, but at a terrible human cost. The countryside was emptier, land patterns had shifted, and the trauma of loss shaped the national consciousness.

Today, Gorta Mór stands as a defining event in Irish history — a moment when economic systems, social inequality, and natural disaster converged with devastating results. It transformed Ireland’s population, economy, and politics, leaving a legacy that shaped the nation long after the hunger had passed.