Long before the world traded with coins, credit cards, or digital wallets, the idea of money itself was already evolving. It was not gold or silver that changed everything, but paper, a fragile material that would eventually reshape global finance. The story of paper money begins in ancient China, where innovation, necessity, and state control combined to create one of humanity’s most influential inventions.

From Metal to Paper

In the 7th century, during the Tang Dynasty, China was already a thriving empire. Trade flourished along the Silk Road, and merchants carried heavy loads of metal coins called cash, round copper pieces with square holes strung together in long chains. These coins worked well locally, but became impractical for long-distance trade. Moving wealth meant moving weight, and that made commerce slow, risky, and expensive.

The first step toward paper money came not from emperors but from merchants. Wealthy traders began issuing promissory notes, handwritten certificates promising payment in coins at a later date. These notes could be exchanged or used to settle debts without the burden of carrying metal. They worked because merchants trusted each other. What began as private convenience soon became a matter of imperial interest.

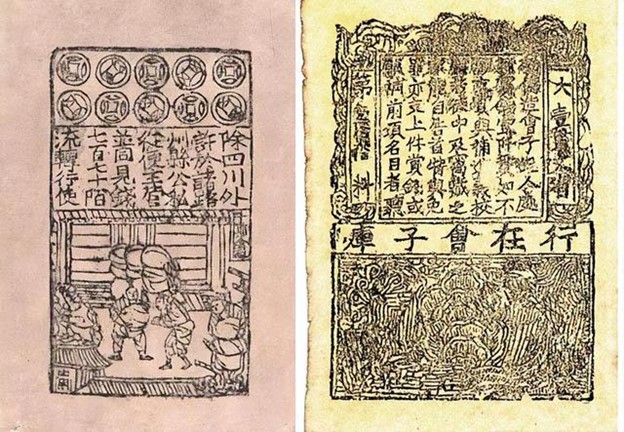

By the 11th century, during the Song Dynasty, the government recognized the efficiency of this system and decided to issue official paper currency. These notes were called jiaozi. They were printed on mulberry bark paper, sealed with red stamps, and backed by the state’s authority. For the first time in history, money existed primarily as a symbol, its value depended not on metal content, but on belief in the issuing power.

It was a revolution of trust.

The Power and Peril of Printed Wealth

At first, paper money transformed China’s economy. Trade expanded across regions, taxes became easier to collect, and large-scale infrastructure projects flourished. The new currency encouraged urban growth and connected distant provinces through a shared financial system. It was lighter, faster, and more efficient than any economic tool that had come before.

But convenience brought temptation. Printing money was easier than mining silver or minting coins, and as dynasties faced military expenses and economic pressure, governments began to overprint. Without sufficient reserves of metal or goods to back the currency, confidence started to erode.

During the Yuan Dynasty, founded by the Mongols in the 13th century, paper money reached its widest circulation and its greatest instability. The Mongol rulers, impressed by the system’s simplicity, used it to finance massive conquests and state spending. Yet with each new issue, the currency lost credibility. Prices rose, and people demanded more notes for the same goods. Inflation, once an unfamiliar concept, became an everyday reality.

By the late 14th century, during the early Ming Dynasty, paper money had lost nearly all its value. Wages paid in notes could no longer buy food, and trust in the system collapsed. The government eventually banned paper currency altogether, returning to metal coins. It would take centuries before the world would reattempt what China had pioneered.

Lessons in Inflation

The Chinese experience with early paper money offers a timeless economic lesson. Currency, no matter how convenient, depends on public confidence. Once that confidence weakens, its value can disappear overnight. Inflation in the Song and Yuan periods was not just the result of reckless printing; it was a breakdown in the balance between money supply and real economic output.

Modern economies face the same challenge in different forms. Central banks today manage digital money rather than mulberry paper, but the underlying principle remains unchanged: too much money chasing too few goods leads to higher prices. China’s early experiment revealed this truth nearly a thousand years before the concept of “monetary policy” even existed.

Yet, despite its failures, paper money represented a giant leap in human financial imagination. It proved that value could be based not only on physical resources but also on collective belief and government credibility, a concept that still defines modern finance.

A Legacy that Changed the World

The idea of paper money eventually spread west through trade routes, reaching the Islamic world, then Europe, and finally the rest of the globe. By the 17th century, European banks began issuing their own notes, inspired by the same logic that had guided the Song Dynasty centuries earlier. From there, the transformation was unstoppable.

Today, when we tap a card or transfer funds online, we are still living in the financial world that ancient China imagined. Paper money and its digital descendants show that the greatest currency is not metal or paper, but trust itself.