Poland has taken a significant regulatory step by approving legislation that phases out fur farming nationwide. President Karol Nawrocki signed the law in early December, making Poland the eighteenth Member State in the European Union to introduce a ban on fur production.

The decision carries particular weight because Poland has been the largest fur producer in Europe and the second largest globally after China. Each year, approximately three million animals, primarily mink, foxes, raccoon dogs, and chinchillas, have been raised and killed in Poland for their fur. These pelts are used in clothing, accessories, and decorative items across international markets.

What the Law Changes

The legislation introduces a phased transition rather than an immediate shutdown.

The law will enter into force fourteen days after its official publication. From that moment:

- No new fur farms may be established.

- Existing farms must cease operations by 31 December 2033.

- Farmers who close their operations earlier will be eligible for government compensation.

- Workers in the sector will be offered support during the transition.

Although roughly 200 to 280 fur farms currently operate in Poland, the sector will gradually wind down over the next eight years. The long transition period reflects the economic scale of the industry and the need to manage agricultural restructuring.

Source: The Fur-Bearers

The Broader European Context

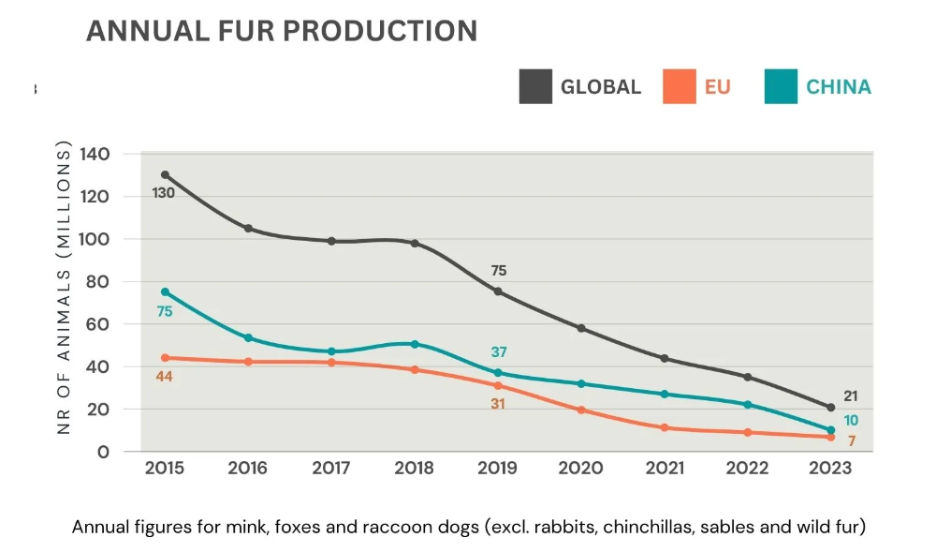

Poland’s move aligns with a wider European trend. Across the European Union and neighboring states, farming has been progressively restricted or prohibited. At the present, more than twenty European countries have introduced either full bans or substantial limitations on fur production.

Despite this trend, fur farming remains active in parts of Europe. Across the EU, more than six million animals are still kept on approximately 1,200 farms. Countries such as Finland, Denmark, Greece, and Spain continue to allow production, although in some cases at reduced levels compared to previous decades.

By removing its own production capacity, Poland significantly reduces the EU’s overall output and alters the geographic balance of the industry.

Scientific Assessment and Policy Pressure

The Polish decision also follows growing scientific and political scrutiny at the European level.

In 2025, the European Food Safety Authority issued a scientific opinion examining welfare conditions on fur farms. The assessment concluded that the confinement systems commonly used for mink, foxes, raccoon dogs, and chinchillas, particularly small wire cages , systematically fail to meet the animals’ behavioral and physiological needs. According to the Authority, the design of current housing systems makes it structurally difficult to ensure adequate welfare standards.

The issue gained further visibility after the Fur Free Europe campaign collected more than 1.5 million verified signatures across the European Union. As a formal European Citizens’ Initiative, the campaign obliges the European Commission to respond and consider potential legislative proposals. The Commission is expected to present its position in March.

Economic and Public Health Dimensions

While ethical concerns have dominated public discussion, the fur farming debate also includes economic and health considerations.

The industry has historically been linked to rural employment and export revenues. However, its profitability has fluctuated significantly over the past decade due to falling global fur demand, price volatility, and changes in consumer preferences.

Public health risks have also received attention. During the COVID-19 pandemic, outbreaks occurred on mink farms in several countries, raising concerns about animal-to-human viral transmission in high-density farming environments. Avian influenza outbreaks have similarly highlighted biosecurity vulnerabilities in intensive animal operations.

Although fur farms represent a relatively small segment of overall livestock production, disease outbreaks in confined animal populations have prompted regulators to consider broader implications beyond animal welfare.

Market Shifts in Fashion

The policy shift also reflects changing dynamics in the fashion industry.

More than 1,600 fashion brands and retailers worldwide have publicly committed to fur-free policies. Several major luxury houses have phased out real fur in recent years, responding to evolving consumer expectations and reputational considerations.

Source: Humane World for Animals

As demand patterns shift, supply adjustments often follow. Poland’s decision may therefore be interpreted not only as a regulatory intervention but also as a response to market contraction within the sector.

What the Decision Means

Poland’s phase-out does not immediately eliminate fur production within the European Union. It does, however, remove its largest producer and establish a long-term exit from the industry.

The eight-year transition period allows existing businesses to adapt, while preventing expansion of new facilities. The inclusion of compensation mechanisms signals that the government is approaching the change as structural reform rather than abrupt prohibition.

The broader implications will depend on forthcoming European Commission actions. If EU-wide legislation is proposed in response to the Fur Free Europe initiative, Poland’s decision may accelerate momentum toward harmonized regulation.