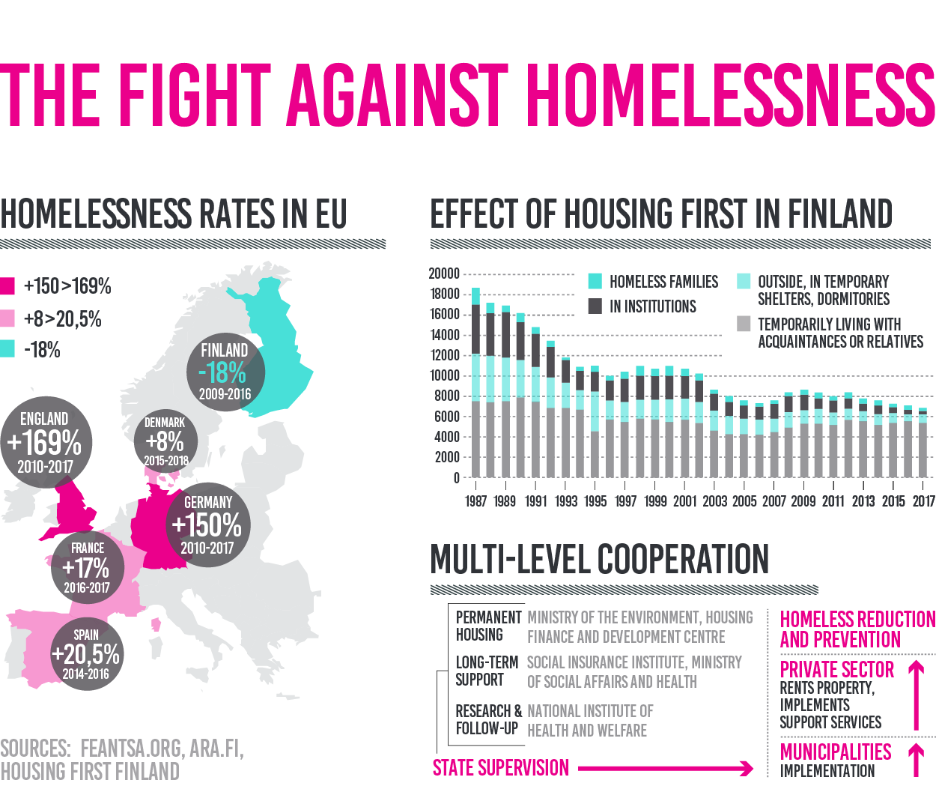

Finland is widely cited as the only European country where homelessness has consistently declined over the past decade and a half. The reduction has not been driven by economic growth alone or by short-term emergency programs, but by a structural shift in how homelessness is addressed. Instead of treating housing as a reward for recovery, Finland made housing the starting point.

Since 2008, homelessness in Finland has fallen by around 35%. Rough sleeping has become rare, and long-term homelessness has declined most sharply. The core of this change is the adoption of the Housing First model, which reversed the traditional logic used in most countries.

The Traditional Model and Why It Failed

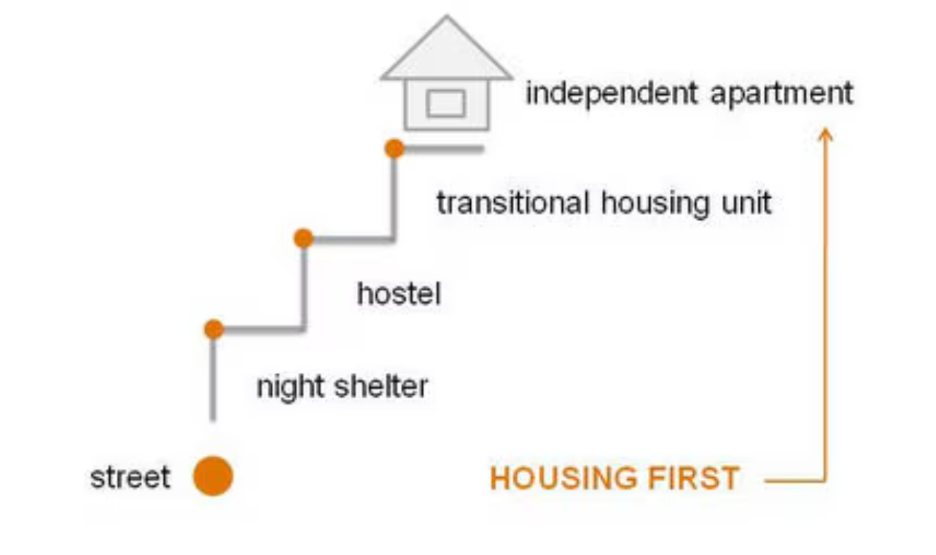

For decades, homelessness policy across Europe and North America followed a staircase or treatment first model. The logic was sequential.

A person experiencing homelessness would first access an emergency shelter. From there, they might move to temporary accommodation, often shared or time-limited. Only after demonstrating stability, sobriety, or compliance with treatment programs would they become eligible for permanent housing.

In practice, the system worked as a loop rather than a ladder.

People moved from the street to temporary shelters, then back to the street, often repeatedly. Emergency shelters were frequently overcrowded, offered little privacy, and imposed strict rules. Temporary accommodation came with conditions that many could not meet while dealing with mental illness, addiction, or trauma.

Because housing was conditional, people who failed to comply with treatment requirements lost access to accommodation. This pushed them back into homelessness, restarting the cycle.

The system was expensive and unstable. People experiencing chronic homelessness made heavy use of emergency healthcare, police services, detox facilities, and short-term shelters. Costs accumulated across public services, but without durable outcomes. Homelessness became managed rather than solved.

The Finnish Shift in Thinking

Finland’s approach was built on a simple but radical change in assumptions. Housing was no longer treated as the final step in recovery. It was treated as a basic prerequisite for it.

Under the Housing First model, a person experiencing homelessness is offered a permanent apartment immediately. The housing is not time-limited and not conditional on sobriety, employment, or treatment of participation. Support services are offered, but they are voluntary and tailored to individual needs.

Source: Housing First.

The underlying principle is that housing is a human right, not a reward. Stability comes first. Recovery and integration come after.

This shift required dismantling parts of the existing shelter system. Large emergency shelters were gradually closed or converted into supported housing units. New apartments were built, and existing housing stock was repurposed for permanent use.

How Housing First Works in Practice

Under the Finnish model, individuals receive their own self-contained apartments, typically with normal rental contracts. Tenants pay rent, often supported by housing allowances, and have the same rights and responsibilities as any other renter.

Support services are delivered separately from housing. Social workers, healthcare providers, and addiction specialists engage with tenants based on need, not as a condition of tenancy. This separation is crucial. Losing housing is no longer a penalty for relapse or crisis.

The model recognizes that addressing mental health issues, substance use, or unemployment is significantly more effective once a person has a stable place to live.

In Finland, much of the implementation has been coordinated by municipalities in partnership with nonprofit housing providers. A central role has been played by the Y-Foundation, the country’s largest non-profit housing provider, which acquires, builds, and manages permanent apartments specifically for people transitioning out of homelessness.

Measured Outcomes and Cost Effects

The results have been extensively documented.

Since the adoption of Housing First as a national strategy, long-term homelessness in Finland has fallen steadily. Rough sleeping has nearly disappeared in major cities. Finland now reports one of the lowest homelessness rates in Europe.

The financial impact has also been significant. Studies comparing costs before and after Housing First implementation show that permanent housing with support costs around 15,000 euros per person per year. By contrast, the previous system relying on emergency shelters, hospital visits, police interventions, and temporary accommodation cost closer to 30,000 euros per person per year.

The savings do not come from reduced support. They come from reduced crisis usage. Stable housing dramatically lowers reliance on emergency healthcare, incarceration, and acute social services.

Social Integration and Long-Term Stability

Housing First has also altered the social trajectory of people who would otherwise remain chronically homeless.

With a permanent address, individuals are better able to access healthcare, apply for benefits, maintain contact with family, and engage with employment services. The apartment becomes a platform for rebuilding routines and social connections.

Importantly, not all tenants fully recover or reenter the labor market. The model does not require that outcome to be considered successful. The primary objective is housing stability, not behavioral compliance.

This has reduced eviction rates and increased long-term tenancy retention. Many tenants remain housed for years, something that was rare under the traditional model.

National Policy and Political Continuity

A key factor in Finland’s success has been political consistency. Housing First was not implemented as a pilot project or short-term program. It was embedded into national housing and social policy, with cross-party support over multiple governments.

This allowed long-term investment in housing stock, social services, and municipal capacity. It also enabled coordination between ministries responsible for housing, health, and social affairs.

Unlike emergency responses that expand and contract with economic cycles, Housing First was treated as permanent infrastructure.

Why the Model Differs from Shelters

Emergency shelters still exist in Finland, but their role has changed. They are used primarily for short-term crises, not as long-term housing solutions. The emphasis is on rapid transition into permanent accommodation.

Shelters are no longer expected to solve homelessness on their own. Instead, they function as entry points into housing.

This contrasts with countries where shelters have become semi-permanent holding systems, absorbing resources without reducing homelessness numbers.

Conclusion

Finland reduced chronic homelessness by changing the sequence. Instead of requiring stability before housing, it provided housing to create stability.

The transition from a shelter-based cycle to permanent housing altered both outcomes and costs. Homelessness declined, public spending became more efficient, and long-term exclusion was reduced.

The Finnish case demonstrates that homelessness is not an inevitable feature of modern cities. When housing is treated as a foundation rather than an incentive, chronic homelessness becomes a solvable policy problem rather than a permanent social condition.