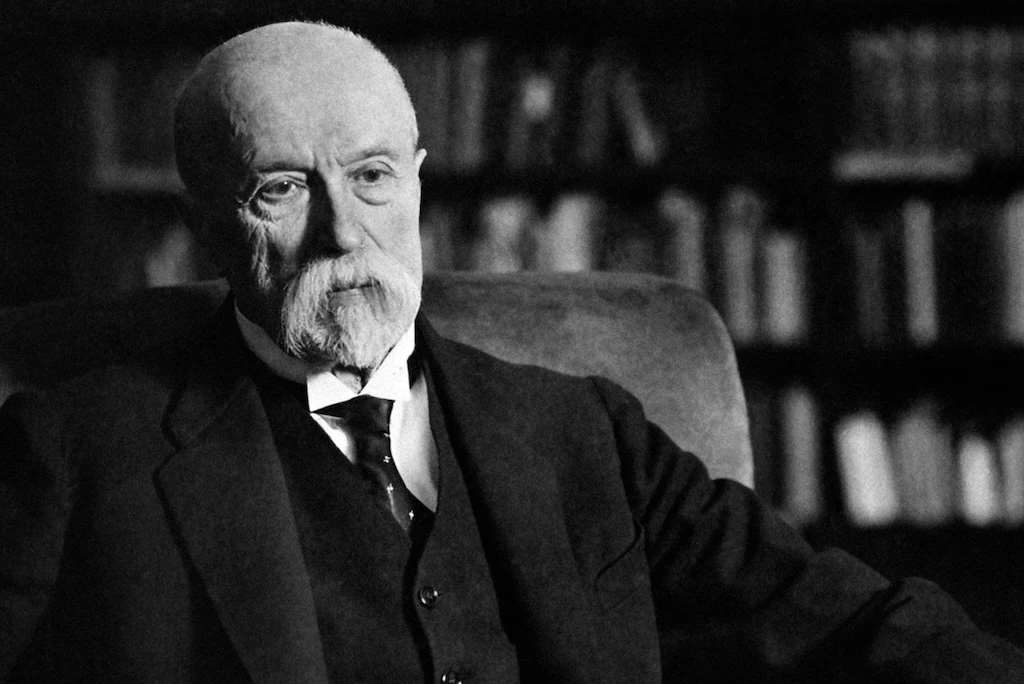

When archivists in Prague opened a sealed envelope from the 1930s, they uncovered words that belonged not only to history but also to the present. The envelope contained reflections dictated by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, the founding president of Czechoslovakia, and written down by his son Jan during the last years of Masaryk’s life. What came out was not a formal political document, but a mix of honesty, irony, and sharp criticism.

The document, now confirmed as authentic in a preliminary analysis, offers a rare glimpse into how the former president saw his own mortality, his political legacy, and the flaws of society. His words appear deeply personal and relevant to today’s debates about leadership, responsibility, and the resilience of institutions.

Facing the End without Fear

Masaryk dictated the letter mostly in English, a language he often used with his family, at a time when he believed death was near. His opening words are blunt: “I am ill, seriously ill. It is the end. But I am not afraid. You will continue the work. You know how, but you must be careful.”

Masaryk’s health had deteriorated sharply after several strokes. By the mid-1930s, it was already clear he could not remain in office much longer. He formally abdicated in 1935 and died two years later, in September 1937. His dictated message reflects that awareness, but also his determination that political work should continue after him.

Judgments on Politics and People

Beyond his health, the text contains observations on politics and society. He singles out Slovak priest and politician Andrej Hlinka, calling him a “fool” for his role in relations with Hungary, though adding, “We must forgive him.”

He also comments on the German minority, a sensitive issue in 1930s Czechoslovakia: “Germans should stay with us. Give them what they deserve, but no more.” Elsewhere he notes: “Czechs are practical workers. Germans have a certain honesty, but they will steal even more.”

His reflections turn to society more broadly: “If people are uneducated and stupid, you cannot do much. People like to be stupid. But do not make it easy for them. Argue with them, argue with them.”

These lines show Masaryk’s unfiltered thoughts in a period of rising tensions at home and abroad, when questions of national unity, education, and political responsibility were at the forefront.

On Death and His “Funus”

One of the most personal parts of the letter concerns his own funeral. “You must make a big funus (funeral). Why make such a fuss? Because I was as stupid as the others. But let them make the funeral.”

On death itself, he wrote with striking lightness: “People are afraid of death, but there is nothing to fear. You only have to buy new clothes, that is all. And above all, the funeral.”

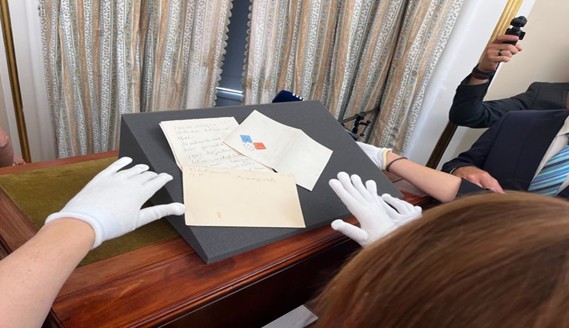

From Sealed Envelope to Public Record

The story of the envelope itself is unusual. It was given to the National Archive in 2005 by Antonín Sum, who served as Jan Masaryk’s secretary, with instructions to keep it sealed for twenty years. The envelope included not only Jan’s handwritten notes but also a recommendation that the text be preserved for posterity.

During the unveiling in Lány, President Petr Pavel remarked that Masaryk was not only a symbol but also a man with human flaws and virtues. His words, Pavel said, remind us that even founding figures should be remembered as real people, not as untouchable icons.

Members of the Masaryk family were also present. His great-grandson Tomáš Kotík summarized the legacy simply: “Live honestly and protect democracy.”